Private python packages in Google cloud artifact registry

Published:

Google cloud artifact registry python packaging

These are some-relatively short but somewhat detailed-notes on setting up a google cloud python packaging index and to have a build automatically execute from a corresponding github repository and push the python package artifact to the google cloud registry.

Step 0: Is this the right step for me?

This is a personal question, you need to ask yourself what your needs and goals are and whether those are aligned with the setup.

If you want to share your code widely with the public then you’ll probably want to put the package into something open like pypi. Publishing your package privately is likely to result in fewer uses though which may not be what you want if you’re making open source software. If you want to ensure the widest distribution and use of your python package, I recommend pypi for publishing.

If you want to test something out and maybe aren’t ready to share it with the world yet, or you’re just interested in using and learning about google’s nice cloud software offerings then you’re in the right place.

Some other scenarios where setting up Google cloud artifact registry might be worthwhile:

You are collaborating with a small team on a startup and do not want the code to be public.

You are building off of existing open source code (say on github) to do a research project resulting in an eventual paper where the code will be one artifact from the project. You do not want someone to scoop your paper or the code so you create a private repository and a private package index. The package remains private until you decide to publicly release the code.

There are probably several more use cases but this gives you a feel for whether this makes sense for your situation or not.

If you are a total noob to python packaging in general then your better off reading the official python packaging user guide first, though the setup shown here might be useful as an example once you grok most of the details described in those docs.

Step 1: setting up an artifact registry …

create a google cloud account and project if you haven’t got them already.

This may require you to have some billing info setup in google, they need to have your credit card info for billing purposes.

You can do all this through the gcloud console, or via code if you have a terraform setup. I’ll work through things via the console-when most convenient-and the cli because the cli is amenable to posting commands in a blog.

step 2: Getting some form of python package setup

Here I’ll use a very simple starter repo that I generate from a python repo template. If you haven’t used github repo templates then I’d recommend you check them out-super handy.

If you plan on making a fair number of separate python packages then it may make sense for you to create a repo template of your own. Otherwise feel free to clone the repo I use in this post.

For the one I used here I started from a template I use that has a starter file with unit tests and also contains configuration for setuptools_scm which uses the git tagging feature to track versions. It’s super handy and something you’ll want to use in some form when pushing and managing versions of your package-either if public or private code.

step 3: Clone the repo locally

This is so that you can make changes, push them to the github remote and ultimately deploy these to the google python artifact registry-a package storage location we’re setting up in this blog post.

git clone git@github.com:rlucas7/python-starter.git

cd python-starter/

pytest # collection should pick up 1 module with 2 unit tests

python3.11 -m setuptools_scm # should see smth like 0.0.post1.dev1+gbd0eece

Note that I have the default setuptools_scm configuration, you can change it if you want a slightly different format or versioning scheme than semantic versioning.

step 4: make a change and confirm you can push to the github remote

Nothing fancy this just fleshes out whether you’ve got all the credentials properly setup with github and your dev machine.

vim src/collections2/add.py # or your editor of choice

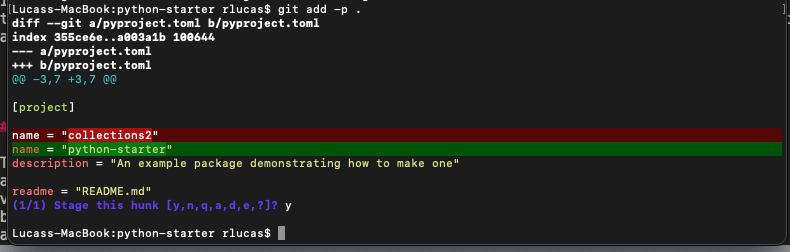

git add -p . # I usually prefer to confirm visually my commits

git commit -m "add module docstring"

git push

Now we’ll also want to setup the github action to run tests. Github actions have a bunch of templates already setup for you so you can use the one they have that creates a python app and runs pytest, easy.

You can check the details of the test run here.

Note: for now I’m pushing directly to the main branch and that is how the github action is triggered. If you’re working with multiple people or follow good development practices you might want to setup the repo so that pull requests (pr), code reviews, and an approval of the pr is required to merge the code to the main branch.

Note: The name of the files and the package name in a template repo in github is not templated.

The consequence of this is that you need to make a commit to change the package name once you make a new python repo from the template. Also, you’ll need to edit the directory structure names for the build and packaging process to pick up the distributed files. When you change the directory structure in the package this also requires a couple changes to the test directory imports, e.g. here.

Forgetting to change the unit test import statements will result in failing tests on the remote. If not the name of the package in the package config or the directory structure won’t match what is in the git repo. These differences make it so you won’t be able to ship the package and install in correctly.

Step 5: Manually publish the package version from dev machine

Basically here all we want to do is confirm you have the permissions to push the package to the package repository.

We’ll first confirm we can see it in gcloud cli, I named mine privatepythonpackages.

Step 5.1 confirm auth and access

gcloud artifacts repositories list # you should see the name of your python package repository

and for mine-yours will be somewhat similar but name and other items may differ (e.g. your chosen location)

privatepythonpackages PYTHON STANDARD_REPOSITORY A package repo for private python packages us-central1 Google-managed key 2024-10-18T16:06:02 2024-10-18T16:06:02 0

Ok now let us setup all the stuff to push. First we do the googley setup stuff

gcloud auth application-default login # authenticate

pip3.11 install keyring

pip3.11 install keyrings.google-artifactregistry-auth

# project-id, repo-name, and location taken from above and google cloud console

gcloud artifacts print-settings python --project=my-project-1948-436821 --repository=privatepythonrepository --location=us-central1

If you try to run something like

gcloud artifacts packages list

you’ll may get an error, that’s expected because we haven’t pushed anything to the python package repository yet so there aren’t any packages to list.

You may want to set some defaults in the gcloud cli config, you can always change these later but for now they make it easy to set things up.

gcloud config set project my-project-1948-436821

gcloud config set artifacts/repository privatepythonpackages

gcloud config set artifacts/location us-central1

Now if we run

gcloud artifacts packages list

again, this time we should see there are 0 items, good that’s expected.

Step 5.2 Build locally and push

Now let’s try building the package locally and uploading

pip3.11 install twine

python3.11 -m pip install --upgrade build

python3.11 -m build # builds the package...

Now you’ll see a wall of text in the stdout and hopefully something like

Successfully built collections2-0.0.post1.dev2+g4a81c16.tar.gz and collections2-0.0.post1.dev2+g4a81c16-py3-none-any.whl

Note: Issue here with the naming

The naming mismatch is that we’ve built the package locally under the templated package name, which is collections2 and really I forgot to change the package name. If you did the changes to the directory and paakcage config (toml file) then you should see the correct package name and not the templated name. If you forgot to make those changes do that now.

vim pyproject.toml # edit the name under the "project" field of the toml file

git add -p .

git commit -m "add name to package"

now after rerunning python3.11 -m build you should see something like

Successfully built python_starter-0.0.post1.dev3+geada567.tar.gz and python_starter-0.0.post1.dev3+geada567-py3-none-any.whl

so the corrected name is now in the build. This matters because you want to refer to the package correctly in your private repo.

Now do the package upload to google

python3 -m twine upload --repository-url https://us-central1-python.pkg.dev/my-project-1948-436821/privatepythonpackages/ dist/*

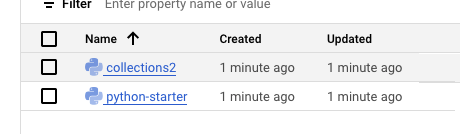

which prompts will push the package to the repository you created, now check in your console that the packages are there, if you have multiple from changing the name like me, then you’ll see these in the console view or you can list them via cli

gcloud artifacts packages list

Lucass-MacBook:python-starter rlucas$ gcloud artifacts packages list

Listing items under project my-project-1948-436821, location us-central1, repository privatepythonpackages.

PACKAGE CREATE_TIME UPDATE_TIME ANNOTATIONS

collections2 2024-10-18T18:04:23 2024-10-18T18:04:23

python-starter 2024-10-18T18:04:23 2024-10-18T18:04:24

Note: For python packages that have more than python code then you can get into issues around building from various operating systems (windows, mac, linux, etc) as well other aspects like if you also have custom gpu kernels. For this post we’re going to say that stuff is out of scope and stick to pure python code. This makes the steps both easier to learn and setup and also makes it so that you can focus on getting the flow of data, files etc. setup and working. This is the workflow I’d recommend to start.

Then once everything is working, add in the complexity of building files for multiple OSes, etc.

If you are already super familiar with all that additional complexity then go ahead but then I’m not sure why you’re reading and working through the steps in this post-we won’t cover the additional complexity stuff here.

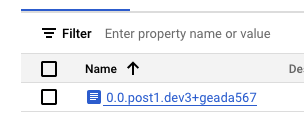

For now we notice that the version in the python packagin index for python-starter has the same mid release version,

python3.11 -m setuptools_scm

# 0.0.post1.dev3+geada567

Note that google will accept a non-release version of the package.

We’ll see how to update this now. It’s fairly simple and described in the readme for the template, using git tags you change these to 0.1 say and then make a commit.

git tag -a v0.1 # I usually add a note in the commit that it's this version

git push --follow-tags # this ensure we send the tag info to the git remote on github

python3.11 -m setuptools_scm # this should now show you -> 0.1 in stdout

Note that if you now rerun the build command

python3.11 -m build

the build will be for a new version with the updated tag info

Successfully built python_starter-0.2.tar.gz and python_starter-0.2-py3-none-any.whl

and if you want to push this to the google registry you can via the twine command and then you’ll have a couple versions populated manually.

Note: Fixing an error on twine uploads

If you get an error on the twine upload it might be because you did not clean out the dist folder so the prior versions are still there. The twine command is uploading all the distributions in that folder so we usually clean it up before doing a new build. The google artifact registry does not allow sending up a package with the same name and version as an existing one so if you have older builds you will want to clean those out first to remove the twine upload error.

rm -rf dist/

python3.11 -m build

python3 -m twine upload --repository-url https://us-central1-python.pkg.dev/my-project-1948-436821/privatepythonpackages/ dist/*

should update the latest build only-assuming it wasn’t already pushed.

I made a second tag so that when I made the github actions workflow in the browser the github action would be triggered on the push. If you look at the history on the git remote in github you’ll notice I forgot to sync locally resulting in a merge commit which dirtied my git commits and tag on the repo.

This will clear itself up once we setup the github action to publish directly to the google artifact package index.

step 6: Step a github action that pushes to the google cloud python registry

This is an optional but highly recommended step. Suppose you’re using some code and you notice a bug somewhere and you want to fix the bug and release a new version. You want this to be a quick and painless operation. O/w it’s going to become a timesink and you won’t fix the bugs, resulting is poor quality code and low velocity. Plus if this is some critical code then you might want to push a hotfix, you can install the package versions that are not “release” versions e.g. <Major>.<minor>.<bugfix> and the setuptools_scm convention with versioning enables these quick releases. You need to add the dev... stuff to the package management tool you are using to manage your python environments. Let’s set it up and make publishing easy.

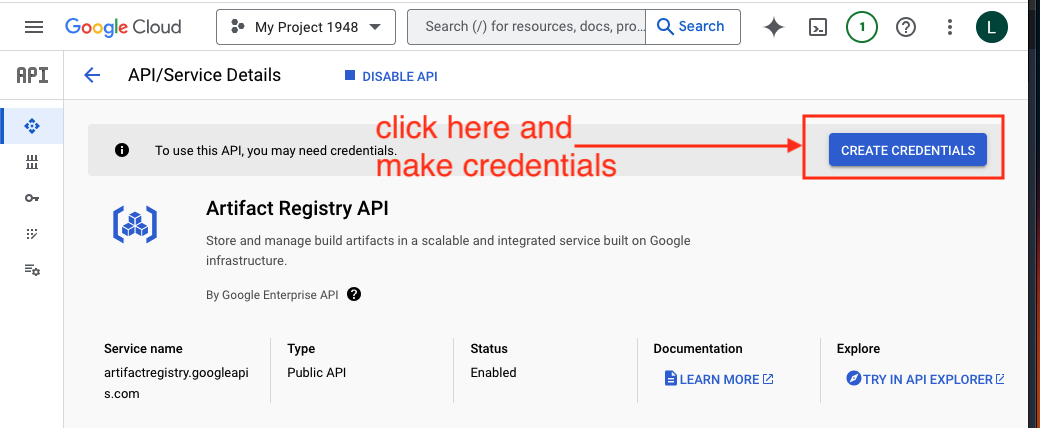

Now in setting up the github action, the key steps are to reproduce the steps you ran locally in step 5 above but now you want them in the yaml file in the github action. You also need to set things up so that the github action has all the credentials necessary to authenticate with the google python repo and push the package.

Step 6.1: Setup the credential file and base64 encode the entire json file in github secrets

The tricky part here-beside avoiding typos-is to put the google auth credentials into the github repo and have them be used effectively.

First create the google auth credentials, creata a service role and then generate the credential file in the google cloud console.

Github supports this via a secrets setup which you can safely use in your github action and the value should not be leaked into public view in the github action logs.

To setup the secret in the github repo you need to have administrator access to the repo. You may find it helpful to read the instructions on github about repo secrets and using them inside github-actions.

When you place the secret into the github repo you need to be sure it is base64 encoded, you can do that via

base64 -i <path-to-the-jsonfile>/my-project-1948-436821-7b5f3e42cdf3.json

copy and past the base64 text that is output to stdout into the secret part in github browser. Make sure that the name associated with the base64 string is GOOGLE_CREDENTIALS otherwise the secret won’t get picked up when the action executes.

Now every time you push to the github remote and you include the --follow-tags flag with an updated tag on the repository, this will trigger the github action to execute and run the build and the push to the google cloud artifact registry.

You may notice that all the credentials in the github action are hard coded/string literals. If you need to setup many google python artifact repositories then you may want to place the names of the roles, google artfiact repositories, etc into environment variabels so that you have a github action template then you would set names/locations/etc in environment variables in the repository on github.

For the purposes of these tutorial notes we’ll skip making a github action as a template. What we’ve done is enough to give you the idea of how to set this up and start hacking. If you need something more production ready then you’ll probably want to modify the setup described here somewhat to better suit your needs-only you have the information to best decide on your needs.

step 7: How to use the package(s) from the google python package repository

Now that we’ve gone through all the effort to package up the code artifact etc. we want to use the code, right? Also if you are collaborating remotely with others who you want to use the package then you need to have them be able to use the package.

Basically installation happens the sae way you use any other package. These are a couple items that can be tricky here though:

If you have a package whose name is the same as a package on pypi, this is generally something you’d be best advised to avoid-pick a different name. Otherwise you can run into confusing conflicts.

You use both open source and private python packages. For the former just pull those from pypi as you typically do, for the latter you need to install these from the google cloud python artifact index.

step 7.1 Authenticate as a python package reader

To install you simply add the url to the python index that you’ve setup in google cloud.

pip3.11 install --index-url https://us-central1-python.pkg.dev/my-project-1948-436821/privatepythonpackages/ python-starter

If this prompts you to login with a username and password then you need to authenticate yourself. You can setup a read only credential similar to the read write credential used in the github action. This requires generating a new access key file etc.

Also, notice that the simple string is included at the end of the --index url, you need to include this otherwise you’ll be prompted for a user login.

For simplicity we’ll reuse the one that has write privileges to show you how to authenticate. It’s basically the command used in the github action but used locally instead.

gcloud auth activate-service-account --key-file=/Users/rlucas/Desktop/my-project-1948-436821-7b5f3e42cdf3.json

you should see something like:

Activated service account credentials for: [github-action-pusher@my-project-1948-436821.iam.gserviceaccount.com]

Step 7.2 Install the package

Now install

pip3.11 install --index https://us-central1-python.pkg.dev/my-project-1948-436821/privatepythonpackages/simple python-starter

If you see something like:

Looking in indexes: https://us-central1-python.pkg.dev/my-project-1948-436821/privatepythonpackages/simple

Collecting python-starter

Downloading https://us-central1-python.pkg.dev/my-project-1948-436821/privatepythonpackages/python-starter/python_starter-0.8.0-py3-none-any.whl (3.4 kB)

Installing collected packages: python-starter

Successfully installed python-starter-0.8.0

then you’ve installed the package successfully.

To confirm you can use the newly installed package open a python REPL via python3.11 and try it out

import python_starter

Troubleshooting

Here if you get an import error, the issue is likely that the directory structure is still under the naming convention from the github repo template, e.g. collections2 and not python-starter.

Unfortunately, as of the time of this writing (Oct 2024) I do not know of a way that the directory structure names can be templated as well in github. If you know how to accomplish that or github changes the way the repo templates work, please let me know via email so I can update the blog post.

The fix here is not too much effort anyway we need to rename the directory under /src and the import line under the /tests/test_add.py module.

Now pushing a tag to the github remote should trigger an updated build to be pushed into the google artifact repo and we can test out the updated version. First uninstall via pip3.11 uninstall python_starter and then reinstall using the command above. If everything was setup correctly you’ll see something like

Lucass-MacBook:python-starter rlucas$ python3.11

Python 3.11.6 (v3.11.6:8b6ee5ba3b, Oct 2 2023, 11:18:21) [Clang 13.0.0 (clang-1300.0.29.30)] on darwin

Type "help", "copyright", "credits" or "license" for more information.

>>> from python_starter.add import add

>>> add(1,2)

3

>>>

Note that here the name add refers to both the module and the function inside the module so it’s a bit confusing.

An exercise for the reader here is to add another operation to the add.py module, the op to add is multiply. Once you’ve added this rename the module to ops.py and update the corresponding unit test as well. It’s also a good idea to add a test for the new op into the test module. If both the test harness and the operations are working, push an updated tag to the remote and uninstall and reinstall the updated version of the package.

Some notes, here for hacky reasons I’m using raw pip installs, if you use a virtual env (a good idea) the same approach works but you need to do the installs in the venvs. If you’re using some other way of doing the environment management then you’ll need to consult the docs for the particular tool that you use.

For learning purposes-if that is your goal-you should make an honest attempt first. For completeness, here is the solution to the exercise for the reader is in this commit.

Found an error, have a question, or have feedback?

My contact info is on the profile panel, feel free to drop me an email.